Marketing, Pleasure and Responsible Choices: In Conversation with Pierre Chandon

Professor Pierre Chandon is a professor of Marketing, Innovation and Creativity at Insead, the top French business school that has campuses in France, Singapore, Abu Dhabi and San Francisco. He is also the Director of the Sorbonne University Behavioural Lab.

His recent research is called Aligning Business, Health, and Pleasure through Epicurean Nudging, or in other words: how to promote healthier consumption choices by emphasizing pleasure. He discussed his research with Areni.

The below transcript has been lightly edited and shortened. To hear the full conversation, listen here.

Areni:

We are going to talk about one of your recent studies, which is called Aligning Business Health and Pleasure Through Epicurean Nudging. Can you tell us more about this study?

Pierre Chandon:

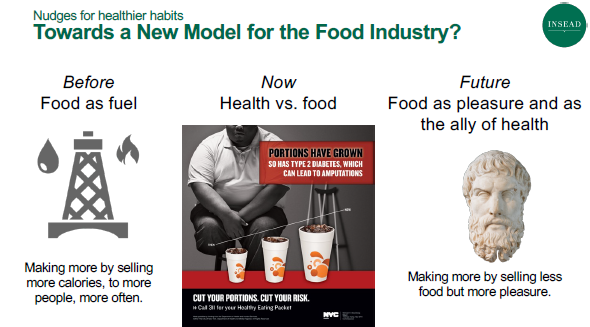

I’ve studied a lot what companies and governments can do to encourage healthier habits and most of the focus is on labelling and, especially, focusing on nutrition and health. And this has been very disappointing overall. It doesn’t work. It works for people who are already healthy, who care about health and nutrition, but it doesn’t really move the needle for the majority of people, because when people choose what to eat or to drink, they focus number one on taste. We’ve been trying to think about how can we talk about taste in a way that encourages better, healthier decisions.

There’s another very important decision, which is how much? We often think of taste and pleasure as the enemy of healthy eating and I think it can actually be the ally. We’ve developed a number of studies — we try to see different ways in which putting taste and pleasure at the centre of the decision of how much to eat and drink can encourage people to actually prefer a smaller, more moderate portion, not because it’s healthier or because of calories, but because it’s actually going to be optimal from a pleasure standpoint. That’s what epicurean nudging is about. We call it “epicurean” because you can trace it back to the philosophy of Epicures who, in 7BC, told his friend in a famous letter that the wise person doesn’t choose the largest amount of food, but the most pleasing.

Putting taste and pleasure at the centre of the decision of how much to eat and drink can encourage people to actually prefer a smaller, more moderate portion, not because it’s healthier or because of calories, but because it’s actually going to be optimal from a pleasure standpoint.

Professor Pierre Chandon

So there’s a lot to unpack in here. You mentioned that the current labelling system that’s supposed to promote healthy eating doesn’t really work. In France, food is rated by health, so they’ve got A, B, C, D, E [rankings]. That system in particular that you’re talking about—it’s not really working?

None of them are really working. We’ve studied the British traffic lights system. The French Nutri score is a bit different because it’s only one grade from A to E, green to red, but also calorie labelling on menus. In a nutshell, it helps the good brands. There are some benefits and, in general, I am favour of them because you cannot be against transparency. I’ve studied them in supermarkets and in fast food restaurants, but the results have been really disappointing, especially in the real world. In surveys, people say, yes, of course I want health. I will change my behaviours. In the real life it’s much more difficult.

It’s not that surprising if you think about it because people who buy the products with the worst nutritional profile already know it. They have shown by their purchase behaviour that they don’t put nutrition as the most important benefits when they choose what to eat, but they will select based on either habits or taste or cost. And so if you tell them that their product is not great nutritionally, well guess what? They already knew it and they’ve shown they don’t really care so much about nutrition, so it doesn’t really change their behaviours.

I’m always surprised there’s a big disconnect between the effect of these labels on consumer behaviour, which is not that big, and the effect on marketers, who are really scared by them and are going to reformulate their food and really lobby intensely against them, even though in reality they don’t change people’s behaviours that much.

You also mentioned pleasure as not an enemy of health, and that’s a totally change of mindset, right? But in our Western context, pleasure has been the guilty thing. You are stating the opposite that pleasure could come with health.

Yes. This is really the crux of the question. Clearly there are indulgent choices and there are healthier choices. Broccoli is not the most pleasurable food I can imagine. I can recognise it’s healthier than ice cream. So this is totally correct. However, this is again focusing on what we eat, which is very important. But then there is a question of how much?

First of all, hunger. Will I still be hungry if I take a small sandwich as opposed to a large one? Fair value for money. That’s a very big driver. And the way the system works right now is that when you buy a smaller portion, you’re taken advantage of. If you go to the movie theatre, if you buy the small popcorn, you’re really feeling that you’re subsidising all the other guys next to you who have this bucket of popcorn and are paying just a few cents more for twice the volume. These are the two factors: hunger, satiation, and value for money, that are driving us to choose bigger and bigger portions without realizing how big they’ve become.

But we forget something very important, which is that the key pleasure in food and beverage does not increase with quantity.

These are the two factors: hunger, satiation, and value for money, that are driving us to choose bigger and bigger portions without realizing how big they’ve become. But we forget something very important, which is that the key pleasure in food and beverage does not increase with quantity.

Professor Pierre Chandon

We all know that the first gulp, the first bite is the most pleasing. You take chocolate mousse or wine. The first one is like this wow effect. The second one is still going to be pleasurable but a bit less than the first. And if you have a really large portion, the last gulp, the last bite will either taste nothing because you are totally oversaturated or it will be a bit too much. You’ll feel a bit queasy about it. The pleasure we get from the whole chocolate mousse is not the sum of the pleasure you get from each spoon, but the average, so the last spoon of chocolate mousse doesn’t add a little bit of pleasure. It actually subtracts from the average. It’s too much. And this is really important.

It’s called hedonic adaptation sensory specific association. It’s not the same for every product, but by and large there is a level at which a larger portion is going to be less pleasurable than a moderate one. And that’s something we’ve studied in France and the US with adults and children. Yet when we ask people their expectations, they don’t get it. They think that a small portion will be too small from a pure pleasure standpoint when it will actually be better than a moderate portion and clearly better than a really large portion.

The pleasure we get is not the sum of the pleasure you get from each spoon, but the average, so the last spoon of chocolate mousse, the last gulp of wine, doesn’t add a little bit of pleasure. It actually subtracts from the average.

Professor Pierre Chandon

But I guess that’s what’s fine dining has understood. When we go into the premium sector, the portion are smaller.

We’ve done a study with school children, a grade school at 4:00 p.m., when you have two kinds of school kids, those who are hungry and those who are starving because they didn’t eat the food at lunch. We found that if you put these children in the mindset of thinking about the sensory pleasure, the aromas, the texture, they themselves chose a more reasonable portion of brownie even though they were either hungry or starving. It’s something that can be redeployed beyond fine dining, where everything from the ambience, the waiters, the napkins and dishes, is reminding us to focus on pleasure. This is something that can be applied even in regular everyday meals.

One of the things that will be different when we study wine, is that when it comes to alcoholic drinks, one of the things that can bias the study is that people want to consume for the effect of alcohol.

Yes, you’re right. I mean it’s a bit like hunger. If you’re really hungry, if you want your stomach to be full or if you really want to get drunk fast, it’s a different motivation and it exists. There are also many people who choose wine for pleasure and not just for social or for other reasons. And I think this is where this has some implications. We need to make sure people realise that all my studies so far has been with food, some studies with sodas. I haven’t really looked at it with wine, but I think the structure also applies to wine. If it’s going to be cheaper, you buy a bottle.

Also anecdotally I’ve seen people telling me, “Oh, I only had one glass of wine, but some of these glasses of wine, they’re so big you can actually pour an entire bottle with it”. So yes, it’s one glass, but it’s actually a lot of wine. The question of what’s a normal amount to drink is not clear in wine. We know it’s not the same in France and the UK and other countries. I’ve seen people with cocktails. I mean they look like fish bowls. They were so big. And I have actually in my office some old cocktail glasses from the forties and they’re tiny compared to what we consider a normal size today. So the question of what’s a regular size, how much am I supposed to drink? I think this very much applies also in the context of wine.

It’s striking here in the UK where you go to normal pubs, the normal size for a glass of wine is 250ml. Those are huge glass of wines and you can end up drinking a bottle without realizing because you only had three glass of wine. And then when you go to wine bars, where the people that selected the wine consciously wanted to focus on pleasure, then it goes down to 175ml or even 120ml, which is the size that we’ve got in France. And what we can do about this without changing the bottom lines of the pub?

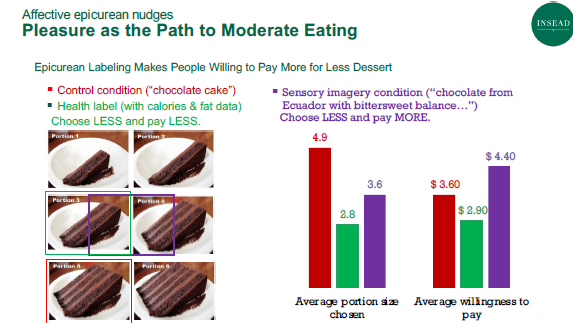

First let me describe the results in France. The study that’s the closest to what you are interested in is a study we run in a cafeteria where we brought people in. It was all you can eat for €15. People could choose as many portions of appetizer, a main course and a dessert as they wanted. And we had three conditions, a regular condition where the food was described in a regular way, plainly. We had a nutrition condition because again, that’s the benchmark. We told them each lemon tart is going to set you back 80 calories and it’s 24% fat. And then we had the epicurean condition. In the epicurean condition we described the food — which was very basic regular food, because for €15 what do you expect — but we described it focusing on the different flavours and aromas.

And what we found was in the control condition, on average, people ate about 980 calories for lunch. And we also asked them at the end of the meal how much they enjoyed the meal. And we asked them what would be a fair price to pay for this meal? And they said €17. Everyone was moderately happy in the nutrition condition. When we told them about calories and fat, we actually had a 30% reduction in how much people ate. I think here people got really scared and when we asked them how much they enjoyed the meal, they didn’t like it. They said it was only worth €15.

And some people were really unhappy about it, especially those who were coming in with friends. They want to have a real meal and suddenly they were counting calories. In contrast, in the epicurean condition, we had a moderate reduction of 16% in how much people ate. And yet even though they ate less at the end of the meal, they said the meal was worth €20. And this is very encouraging because it means we have a win-win win in the sense that people eat more moderately but not too little.

They ate less, but they had a better experience overall. In this cafeteria we had cameras that allowed us to monitor the speed at which people were eating. And what we found is that in the epicure condition, people ate more slowly. They stopped looking at their phone, they focused on what they ate because it was supposed to be this incredible food, and they expected the food also to taste better. It’s not rocket science. It’s something the gastronomic restaurants have known all along. If you put people in the right mindset, you can actually get people to pay more attention to pleasure and as a result prefer a smaller portion and be happier with it.

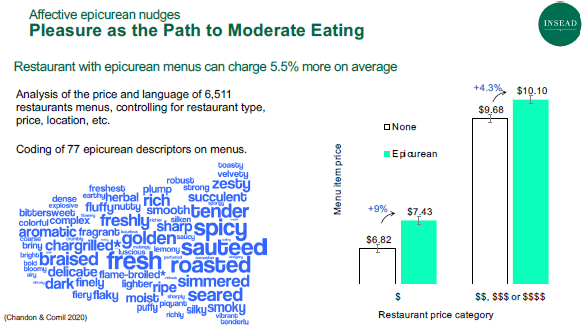

In another study we looked at the menus of thousands of restaurants in the US. And we found that those restaurants that use these sensory words on the menu to describe their dishes were able to charge 4% to 5% more on average. And this effect was actually stronger among cheaper restaurants than among the really expensive ones. Because among mom-and-pop restaurants, typically the focus was either very plain or focusing on quantity. So I think this idea of epicurean labelling and nudging is not something that has to be on the purview of expensive restaurants. It’s something that can be used also all across the restaurant.

We found that those restaurants that use these sensory words on the menu to describe their dishes were able to charge 4% to 5% more on average.

Professor Pierre Chandon

In the world of wine, we’ve been criticizing or challenging the language and all the elaborated words that we use to describe wine. If you build an environment that focuses on pleasure and sensory pleasure and bringing people to actually pay attention to what they drink, they will drink less and they will pay more, which is basically what we want.

This is a study that remains to be done, but I believe it should work. You’re right that the menu is just one way to the description — the ambience, everything can be used. And now the bad news is that it’s not a magic bullet. We found this effect worked much better in France, for example, than in the US. We haven’t done this in the UK.

Why did you think that was?

I think this idea of savouring and quality goes with moderation and is something that we know in France. In the US there’s more of the idea that big is beautiful. For example, there are studies that are asking people: if you have a certain budget, you can have three days in a hotel that will have this amazing experience, or you can make it last seven days. And so the Americans will go for quantity and the French for quality. This is something that’s beyond food that we’ve found in different domains. And there’s also, if you say ice cream and ask Americans what comes to mind, they’ll say fattening. And the French will say delicious. If you ask people in France and the US to define eating, well, most of the French will say, “Oh, it’s eating something of high quality that you really enjoy”. Whereas the Americans will say more about, it’s about nutrition and carbohydrates and things like that.

There’s a part of your study that focus on packaging sizes and moderation as well. In part of the study you say that healthy eating is mostly a ‘doing’ problem. I was wondering if you could elaborate on this.

We tend to have this idea that healthy eating or drinking is mostly a knowledge problem. If we just were able to educate people about what’s healthy and what’s not, then the problem would solve itself. And I don’t think that’s true. I don’t think anyone really needs to be reminded that ice cream is full of sugar. Okay, there are cases when, of course knowledge matters, but mostly you and I know that we’re supposed to drink more water and eats less indulgent food.

I think it’s more of a question of, “OK, I know what I’m supposed to do, but it’s hard to resist temptation because the cost is now, the benefits are in the future”. And that’s why I think instead of trying to reformulate the food and create all of these Frankenfoods that many people actually don’t like, what we need to do is try to work with the food and drink that people know and love and try to find a way to encourage them to choose a regular portion. For the first 60 years of its existence, Coca-Cola only had one bottle of 6.5 ounces, and if you wanted more, you bought two. A regular portion today will be more than twice as big. And you can go to this convenience store, to the movie theatre, you can have a full litre cup or even some as big as two litres. So they’ve increased tremendously in size, but it also means that we don’t really know what’s a regular cup size anymore. And so the big insight here is that because we don’t tend to think too much about how much to drink, we tend to choose based on what’s offered to us. But now if the range of sizes goes up to two litre for one cup, then what’s a normal, we don’t know.

We’ve done studies where we find that just adding a smaller size to the range, it changes our reference, it changes the way we are actually going to categorize the sizes. And the old small is now a new medium, and as a result, more people are going to choose it and people will be willing to pay more for it.

We found that just adding a smaller size to the range changes our reference. It changes the way we are actually going to categorize the sizes. And the old small is now a new medium, and as a result, more people are going to choose it and people will be willing to pay more for it.

Professor Pierre Chandon

How can we use this to enhance the experience of the consumer and reduce the intake of alcohol without the restaurant losing anything?

Rituals are really important and I think they can be helpful to encourage moderation if they encourage people to slow down. And that’s again, that’s the key. It’s to savour. If we drink or eat too fast, then we don’t even register how much we’ve drunk and then we’re going to order another one. And then this is where the problem starts.

I know a study about water where they ask people to drink water and every sip becomes less and less pleasurable. But if you ask people to drink this water every time in a different way, every new sip is now a new experience. You’re starting from scratch, from zero, and you enjoy it as if it was the first.

What are the next steps for this study?

One study is looking at how being close to nature can also encourage people to choose healthy food. We’re looking at the effects of preservation containers for food like doggy bags, but also for wine. And our idea — and that’s something we’re testing — is that if you mention it on the menu at the very beginning, there can be a win-win.

What we found was that it led people to order more food because now they can actually do meal planning and say, okay, maybe I’ll order more food and then bring it back home. Or even I will order the bottle instead of only a glass or two. I can drink it later.

It’s a win for business, but it’s also a win for health because what we found is that it encourages moderation because no one likes to waste wine or food. And so when you have a big portion, you feel like you have to eat it. Then when you know can easily carry it out with you later, then you only eat what you really want and bring the rest back home. I’m very excited about this idea.

Additional Resources on Wine & Health:

- The Responsibilities Series – Episode Two: Wine & Health

- Fine Wine and the Social Contract

- Fine Wine, Health and Wellbeing – In Conversation with Rebecca Hopkins

To keep in touch with our research, analysis and events, subscribe to our newsletter.