Inside the World of Wine Investment: In Conversation with Rostislav Petrov and Matthew Small

London-based Cru Wines was founded by Gregory Swartberg in 2013, as a platform for wine connoisseurs and collectors. Today its team includes sommeliers, engineers, and financial advisors, and using a digital-first approach. Cru caters mainly to private individuals at the high end of the market, where the average bottle price is £200-plus. Pauline Vicard, CEO of Areni Global, spoke to Rostislav Petrov, Associate Director and Matthew Small, Senior Portfolio Manager.

Areni Global:

What’s your definition of the secondary market ?

Matthew Small:

For us, the primary market is direct from the chateau or the domain or the producer. Then the secondary market is anything that’s traded subsequent to that.

How do you fit into that secondary market? What’s your place?

Matthew Small:

We get allocations from the primary market, but then we also trade in the secondary market. We would look at back vintages; maybe we will price them based on our kind of fundamentals and then see are they under-priced versus where we think they should be or where we think they could go in the future.

Rostislav Petrov:

We are here to advise our clients, to give them direction, to let them try new wines and explore the different new regions. And it does mean that we have to sharpen our knowledge and go and visit Austrian producers and taste the wines and perhaps organize the tasting with some of those clients for them to discover this specific wine region. It definitely helps to push some of those up-and-coming regions into clients’ portfolios and to get that acknowledgement of the quality of the wine from the wines which we never really tasted before.

Who are your clients? What type of people are you working with in terms of gender, in terms of age, in terms of geography?

Rostislav Petrov:

Our headquarters are in London and, naturally, the majority of our clients have a base in the UK. We also provide services to a number of collectors and connoisseurs from around the world, especially when it comes to full portfolio management. However, most of the wines will still remain professionally stored in the UK.We work with a third-party provider, the oldest company in the UK, to provide such a service.

The wine industry is very traditional and it remains male dominated. However, we do see more and more women getting involved, which I think is great. I don’t want to make up numbers, but I was in the company for the last four years and I do have more and more female clients. I mean rightly so, because statistically women are much better tasters when it comes to wine.

What differentiates [your clients] from one another?

Matthew Small:

I think motivation would be the best way to segment them. And there’s a spectrum — people who just want to drink and then people who just want to invest. But the majority are somewhere in between. They’re investing a little bit or they’re collecting, but looking for wines to drink now and we tailor the service to meet that client’s needs.

Motivation would be the best way to segment [consumers]. And there’s a spectrum — people who just want to drink and then people who just want to invest. But the majority are somewhere in between.

Matthew Small

Whenever we acquire or speak to a new client, we work out what their needs are. We’ll have that initial discussion with the client and see what exactly they want and what part of the business is fitted to suit that client’s needs. The other thing as well internally, we all kind of speak to each other. So I mean I specialize more in the investment side, but regularly speak to the private client team and vice versa. If they need some information on the wine market, they are very clued up themselves, but if something’s very specific, they come to me and we just really want to provide the best service possible for the client.

There are a lot of people that hate wine investors because they see them as people that absolutely have no interest in wine. Is that the case?

Matthew Small:

We do get people who solely buy wine to invest. And they’ve obviously been attracted by the low volatility, no capital gains tax, fairly consistent returns. And that is their pure focus. But the majority of our clients are a mixture of both. They enjoy wine, it’s a pastime of theirs and that’s maybe what’s attracted them to wine investing as kind of a follow on from their hobby. So it’s a real mix.

Most of our clients that store wine will sell some and drink some. So I think that the definition between collecting and investing is a little bit blurred.

Rostislav Petrov:

It’s difficult to draw the line. It’s a bit of a grey area. A lot of people who invest in wines, do enjoy a very good bottle of wine. [In] the UK system — that bonded warehouse — you don’t physically have access to those wines. When you store them and you see the prices are going up, you can’t just open a case and get one of the bottles out of the case and drink it.

Is there a definition for wine investment?

Matthew Small:

Well, when we look at an investment wine, they’re definitely in what people would probably regard as the fine wine bracket. We look at things that I call fundamentals. So the first thing would be brand. So that would be a producer that is well recognized and has had consistent production over a number of years.

When we look at an investment wine […] we look at things that I call fundamentals. The first thing would be brand. So that would be a producer that is well recognized and has had consistent production over a number of years.

Matthew Small

The First Growth classification would be the well-known one. Right Bank, the top domains in Burgundy, Grand Cru, Premier Cru. And we have an idea of who those top producers are, often by price, but not always. Another way we’d look at it is Liv-ex have their own way of identifying the top producers based on trade value and a number of other things. And then we kind of have our own individual metrics that we track to check momentum of brands based on price performance. We can track which brands have strong momentum and which don’t.

The power of the brand is based also on the consistency, the history, but you also mentioned the quality as well and the critic score. Often a question that we get is: How important are the critics’ scores?

Matthew Small:

Quality would break down into two parts. First off would be the critic’s score, and the second is vintage. The reason why we look at both is, if we were to have a 100-point wine from a good vintage or a well-regarded vintage and a 100-point wine from a less regarded vintage, the good vintage will be more expensive despite having the same critic score.

Quality would break down into two parts. First off would be the critic’s score, and the second is vintage. If we were to have a 100-point wine from a well-regarded vintage and a 100-point wine from a less regarded vintage, the good vintage will be more expensive despite having the same critic score.

Matthew Small

Although it’s a subjective score, it gives us some measure to quantify the wine.

How big is the discrepancy between what the critics have predicted and what the market has shown?

Matthew Small:

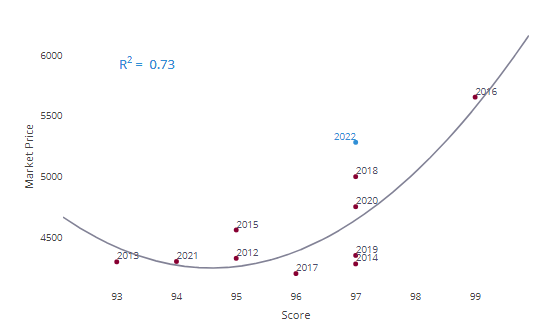

We can actually break down the accuracy of critics’ scores. If we look at the market price versus the critic’s score of say the last 10 vintages, you can then work out how accurate they have been in the past and whether that’s the best critic score to use to identify the value of the wine.

We can actually break down the accuracy of critics’ scores. If we look at the market price versus the critic’s score of say the last 10 vintages, you can then work out how accurate they have been in the past and whether that’s the best critic score to use to identify the value of the wine.

Matthew Small

We use what is called “a fair value analysis”, determining if the critic’s score is aligned with the market price. We would not use this as a sole determinant of an investment’s potential but use this alongside our fundamentals and other valuation tools.

The R squared value (blue), determines how well the regression model explains observed data. In this example Neal Martin’s scoring determines price with 73% accuracy. Cru only use a critic with an R squared value of > 0.7

How many critics are you tracking today?

Matthew Small:

We have our preferred critics for certain regions. If we’re looking at Italy, we’ll look at Antonio Galloni and Monica Larner and then we can then track basically how their scores have correlated with price. And then we have a kind of good idea which critic we should be using for which region and why.

And the same thing for Bordeaux.

Rostislav Petrov:

Jane Anson, James Suckling, William Kelley from Wine Advocate, Neal Martin and Antonio Galloni from Vinous.

Does a wine need to be able to age in order to be investment worthy or is it more like a consequence just because it’s good quality than it’s going to age?

Rostislav Petrov:

For sure. The quality of the wine is often linked to its potential to age and wide. A very simple rule as to why the price of the wine goes up is because 20 years later, out of 10,000 cases that were produced, 8,000 were drunk and the whole market is only left with 2000 cases, meaning that demand is so much greater. So the ability for the wine to age is definitely very important.

A very simple rule as to why the price of the wine goes up is because 20 years later, out of 10,000 cases that were produced, 8,000 were drunk and the whole market is only left with 2000 cases, meaning that demand is so much greater.

Rostislav Petrov

And so we’ve seen your definition of an investment wine. How many wines do you fit into that category?

Matthew Small:

I mean we would be in the hundreds and I think if we look at the Liv-ex sub-indexes there are a thousand; the majority of the wines on that index would fit our criteria and meet our fundamentals.

When you look at those investment wines, it’s easy to see that the majority of them come from Pinot Noir, Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay. Why is that?

Rostislav Petrov:

I see there are two main reasons for that. So Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay — and I would probably add Merlot as well —are easy to understand. They are more predictable and deliver joy to the consumer even if the drinker doesn’t have a great deal of experience tasting fine wines.

Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay — and I would probably add Merlot as well —are easy to understand. They are more predictable and deliver joy to the consumer even if the drinker doesn’t have a great deal of experience tasting fine wines.

Rostislav Petrov

How much do you need to know about wine to invest in it?

Matthew Small:

First off, if you’re going to get into wine investing, do your research, speak to a number of different brokers and then find someone you can trust. Back in the day, it was just a small number of brands and the experience you needed from a wine and investment knowledge isn’t as vast as you need now. The way we look at wine investing is a lot more how traditional assets would be valued by institutions.

We would ask similar questions as to what a wealth manager would ask: What’s your time horizon, what’s your risk profile, and what’s your budget? And then we will basically tailor a portfolio around those kind of requirements.

When we’re building a portfolio for a client, say they’re traditionally very low risk with what they do in their other investments, well then we might be a lot more Bordeaux heavy. If they want to take on a bit more risk, we would look at regions like Champagne and Burgundy. But we don’t just look at risk, we want to look at return as well.

Wine is interesting as an investment because the level of risk is relatively low compared to other things and it still offer a very substantial return. What makes wine a stable investment?

Matthew Small:

Maybe fewer people are investing in wine, which maybe makes it less volatile. The price is also maybe held more by merchants, so the sales price is more stable.

If we look at individual wines, it’s the play between demand and supply. So when they’re in their perfect drinking window, they’re also at their scarcest, but demand is also higher because they taste better.

But then if we look at the market as a whole, you’ve got increased demand from people knowing more about wine. So as the [knowledge] of wine is growing, you’ve got the premiumization effect. So we’ve seen that millennials and Gen Zs are potentially spending more per bottle than generations before, so more demand for fine wine. And then we’re seeing the number of Ultra High Net Worth and High Net Worth Individuals increase throughout the world. So that’ll be another impact on demand.

There is no correlation between how wine investment performs compared to how the S&P 500 performs. But something that we are actually seeing at the moment is that currency and interest rates have an impact on the fine wine market. Why is that?

Matthew Small:

Basically, there’s a strong inverse correlation between interest rates and the price of wine.

So the higher the interest rate, the lower the price on the market.

Matthew Small:

Exactly that. And there are a number of reasons for that. First off is sterling. The baseline currency of fine wine is actually pounds sterling. The reason for that is the majority of the indexes are based in the UK and the majority of the biggest merchants are in the UK as well. That means when sterling goes up in value relative to other currencies, the cost of fine wine goes up as well. So the UK interest rate is the main determinant of the value of sterling.

The baseline currency of fine wine is actually pounds sterling […] That means when sterling goes up in value relative to other currencies, the cost of fine wine goes up as well.

Matthew Small

If interest rates are 5.5%, you can then put your money risk-free into a bank and you will earn 5.5%. And if the average return for fine wine is 7.2%, then you’re only getting 1.7% return for taking on some risk in that asset class or that investment. Well, if interest rates are down at 2.5%, that risk premium then becomes a lot more attractive.

Traditionally, Bordeaux had the lowest standard deviation or risk. For the first time ever in 2023, Italy had the lowest standard deviation, meaning that Italy (driven by Tuscany) is now the region that brings the most return for the less extra amount of additional risk.

What would be the main reason for a wine to be overpriced or under-priced?

Matthew Small:

There are a number of ways we compare wines. First is a Liv-ex tool called Fair Value. Basically it uses similar method that we talked to earlier comparing critic scores to market price. Any of the vintages above the line would be considered overpriced and vintages below the line may be considered under-priced to that. That’s kind of a good proxy. Then there’s other ways of looking at wine. So for example, we talked about looking at the accuracy of a critic and if this critic shows good accuracy in predicting or his scores or her scores match the value of the wine, you can then calculate price per point and then use that as another proxy to value or compare wines.

Another way of doing it is comparing the value of the wine to back vintages. Say a new vintage is a similar point score to a vintage of say four or five years. These are all different things we will look at to determine if a wine is good value or not.

When we were doing our Singapore reports, a lot of the people we interviewed mentioned you and mentioned that young people were attracted to the gamification part that comes with wine investment. Could you touch on that?

Matthew Small:

Sure, and I think a lot of this actually came from crypto, because buying and selling crypto wasn’t as simple as buying and selling traditional asset classes. You had to teach yourself how to get an account, how to use an exchange. They also had security keys and codes and things that were completely new to how retail investors had traded before, and that kind of knowledge then give them a bit of financial acumen to apply to other asset classes and also explore asset classes. Younger investors are far more interested in investments.

But what makes it fun?

Matthew Small:

I think it’s more of a passion asset. So I mean the joy of wine and wine investing is the amount of work over time that’s gone into making such a niche product that can only be made in that one part of the world under certain conditions. And I think that and the story behind the families and the brands and that background adds a bit more to the investment as opposed to just owning a company got good cash flows.

Rostislav Petrov:

If I may add, I think it’s also a lot about memories and experience. Once you go to visit the vineyard and you have that glass of wine while watching a sunset, it gives you some set of memories, emotions. Every time you see that case or bottle on the screen, it kind of brings that back.

These interviews have been lightly edited and condensed for clarity. To hear the entire thing, listen to the podcast.

Additional Resources on Finance:

- Analysis: Can Fine Wine Be Scaled?

- Money, Profit and Financial Sustainability

- How the Energy Crisis Threatens the Future of the Glass Bottle – In conversation with Adeline Farrelly

To keep in touch with our research, analysis and events, subscribe to our newsletter.