How To Be Extraordinary: In Conversation with Dr. Kiko Thiel

After watching an extraordinary performance, Kiko Thiel asked an extraordinary question: What’s the difference between an excellent performance and an extraordinary one? What makes someone great, rather than merely good? Today, Thiel is an expert on how people manage to do extraordinary things, even at a great personal cost. Her research has uncovered the ways that people rewrite what it possible, setting off into new territory, and rewriting the paradigms as they go. Previously, she worked at McKinsey, Accenture and for the INSEAD Blue Ocean Strategy Network. She has an MBA from INSEAD and a BA in history from Yale.

Thiel sat down with Areni Global to reveal the differences between excellence and greatness, and how someone can move from one to the other.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity. To hear the entire conversation, listen to the podcast.

Areni Global:

Tell us about your research, and what led you to do it.

Kiko Thiel:

The whole catalyst for this research happened when I was watching the Paralympics during the 2012 London Olympics. I was watching a Chinese swimmer, and he won the Gold medal and set a world record in the backstroke. He also won a Silver medal in the butterfly. And when he came out of the pool, I realized he had no arms. I was in my living room watching on the TV, and I just stood there in my living room looking at this, my jaw hanging, thinking, “How is this possible?” What makes people do these extraordinary things?

At the time, I was a management consultant working in leadership, organizational change and innovation, and organizational behaviour. I started talking to people and everyone thought it was a fascinating question. Everyone had ideas and got really energized, but everyone had different answers. I finally decided I really want to get to the bottom of this. I took time off to do a PhD.

What did we know about greatness before your research?

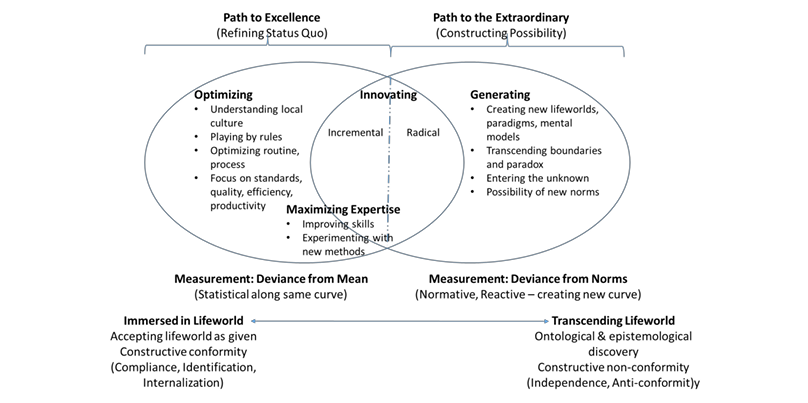

A lot of people talk about excellence, in business or in education or in sports. There’s so much research done on excellence. What I found was very little done about ‘extraordinary’, which I defined as deviating from the status quo, going into the unknown and creating a new possibility or new reality.

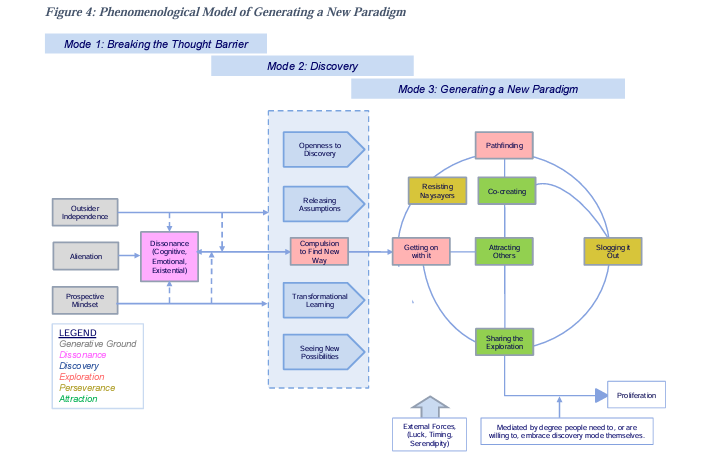

When it came time to define this in the academic context, I used the term ‘transformative change’. The easiest way to think about it is creating a new paradigm. If you create a new paradigm, you’re creating a platform of possibility that other people can build on. People are able to see the world in different ways and suddenly they see new possibilities.

If you create a new paradigm, you’re creating a platform of possibility that other people can build on. People are able to see the world in different ways and suddenly they see new possibilities.

Kiko Thiel

I finally decided that there’s greatness or exceptionalism, but excellence really is about staying within the status quo and striving harder, whereas extraordinary is creating a new paradigm.

What fields helped you frame your research?

I couldn’t find anyone who’d done research on this topic, which surprised me. Even in innovation, they tend to look at incremental innovation. Sometimes you’ll see some books on radical innovation, but there was very little on paradigm creation. I started off in the management literature, because I thought there should be lots of literature on different kinds of performance. But then I started to realize that I needed to understand what makes people deviate from the status quo. So then I started looking at deviance, [which] is normally considered negative.

Looking at how sociologists looked at it was helpful, because they identified three ways of looking at deviance. So there’s the statistical, the normative, the reactive. The easiest way to think about is statistical is measurable, quantitative normative is qualitative, and the reactive is how people respond.

In the management field, there is a school called positive organizational scholarship and it was developed amongst professors at the University of Michigan, and they said, we should be looking at positive deviance. Deviance doesn’t have to be negative — it can be positive as well.

So sociology is one of the fields that helped you frame the study.

The other big one was social psychology. Social psychology talks about conformity and non-conformity. One of the sad things about academia is that these different fields hardly ever talk to each other. I was one of the few people who was looking at both literatures. The social psychology aspect is actually really important because so much research has been done on conformity, but not on non-conformity.

What we do know with non-conformity is that you could be revolting against social norms, but there’s also what’s called independence. And this was a concept that became very important for my research, in that I found that most of the people that I researched weren’t reacting against something, they just had their own independent outlook. Conformity comes in many guises. There’s social conformity; you don’t want to be thrown out of group. It’s a survival mechanism. But there’s also intellectual conformity, where you think, “Well, I don’t know so much about this.”

But there are certain individuals who just find their own way and they ask probing questions. They don’t take anything for granted. And it’s these types of people who are able to see things differently.

There are certain individuals who just find their own way and they ask probing questions. They don’t take anything for granted. And it’s these types of people who are able to see things differently.

Kiko Thiel

A lot of these people felt like outsiders. I call it ‘outsider independence’. They may have been immigrants or women in a man’s world, but they found that the status quo didn’t necessarily reward them. It gave them an independent perspective.

Is independence a dissonance from the norm?

I talk about as sort of a specific moment or a series of moments when something happens to them and they suddenly think, “Wait a second”. A lot of people make ground-breaking discoveries because there’s a cognitive dissonance, and rather than shake their head and walk away, they then look further into it and discover something new. But there can be emotional dissonance and there can be existential dissonance.

I found a number of people in life-or-death situations where they thought, “This can’t be right. There must be another way.” Or someone is dying and normal norms don’t matter anymore. It frees them to look at things freshly.

The dissonant moments tend to be specific moments that prompt someone to explore further, and that’s where they discover over time — and it takes a lot of exploration and questing — that actually, yes, there is a different way to do things. There is a new paradigm here.

The dissonant moments tend to be specific moments that prompt someone to explore further, and that’s where they discover over time — and it takes a lot of exploration and questing — that actually, yes, there is a different way to do things. There is a new paradigm here.

Kiko Thiel

So dissonance might lead to independence, but independence doesn’t mean extraordinary every time.

Some people will have developed this outsider independence over time, especially through childhood. There are other people who they enter adulthood and they have some sort of alienation that starts to give them this outsider independence. But usually there’s a dissonant moment. Someone with outsider independence isn’t necessarily going to create a new paradigm. I’m sure they’ll ask lots of interesting questions and do lots of interesting work, but they may not necessarily create a new paradigm. For example, Jane Goodall is someone who I don’t think necessarily had a dissonant moment, but she had something which I call ‘newcomer innocence’. She came into a field without any of the training in zoology or animal observation, so she saw things very freshly.

When we’ve done our research on what makes a fine wine, we came to the conclusion that it’s a collective definition and it’s what was called the ‘community of taste’. People agreeing about something. And within that category, within the community of taste, we’ve identified eight categories of people that have an influence on that definition. One of them we’ve called the ‘outsiders’.

And I think that fine wine is probably more a pursuit of excellence than the extraordinary, because you’re dealing with physical things that are unchangeable, right? It’s a craft.

It’s a very interesting debate about whether fine wine is a quest for excellence and extraordinary and whether it’s a craft or not. But I just wanted to go back to my original question — how did you conduct your study?

Obviously I had to do a lot of reading. First it was management literature, innovation literature and sociology, social psychology. Then neuroscience, because it turns out that the behaviours used for excellence — goal setting, attention to detail, planning — all happen in one network in the brain, the task positive network. Whereas curiosity, imagination, thinking of a world that doesn’t exist, operates in a wholly different network, called the default mode network. So I realized that these behaviours are operating in different sides of the brain. I think it helped me feel that this is an important distinction. So then I created criteria for what it means to be extraordinary. Does it challenge those who are in that field? Does it challenge their notions of what’s possible or even challenge their notions of reality? I looked for people in different fields. So it wasn’t just business, it was in education, it was in academia.

What I stayed away from was science, technology and the arts, because then there’d be so many variables. I decided, let’s put those aside, even though they’re fascinating.

I started interviewing people. I wasn’t able to interview everybody, but the people I included in my studies were always people where there were primary materials of interviews, autobiographies, letters. It was very important for me to understand what was going on in their head. I didn’t want to just say, factually, this is what happened. I wanted to know what were they going through — why did they deviate from the path?

There’s a sense of curiosity. I think a sense of wonder is very important. I call it going into the discovery mode and they don’t know what they’re going to find, but they’re so engrossed in discovering, and then it does take them somewhere.

One of the difference that I hear you say is that you can decide to be excellent. That can be a conscious decision: I’m going to be excellent. I’m going to be the best at my field. But being extraordinary is something that you can’t really wake up someday and say, I’m going to be an extraordinary person and I’m going to change the world.

You are absolutely right. And I’d never really put my finger on that particular aspect of consciousness in terms of consciously saying, ‘I want to be excellent’. I don’t think anyone thinks, ‘Oh, I’m going to be extraordinary’, but it’s a mindset that might take them there.

Is the capacity to be extraordinary nature or nurture?

I think a lot of it is nurture. There is something called prospection. This is the ability to imagine a world that doesn’t exist and to imagine in a way that is real to you. It’s so real to you when you’re describing it to other people, you can see how that can excite them because you’re able to speak of it in such a vivid way. We know what part of the brain is activated when people are using prospection. And it’s very definitely in the default mode network.

We don’t know if prospection can be nurtured or not. Someone like Elon Musk obviously has a very great talent and he talks about how when he’s thinking, he can see it vividly. He obviously has a great capacity for prospection. There’s another thing: we have these two networks in the brain and it’s not clear that one can use both networks at the same time. What we suspect right now is that one has to toggle back and forth between them. I think some people are better at toggling back and forth. Is that something that can be learned or not?

It turns out in order to do something extraordinary; you have to go into that discovery mode. You have to go into the unknown. And that’s very different from excellence behaviours. But once you’ve discovered something, you need to switch back into the excellence mode. You need the perseverance to create something extraordinary.

I’d like to go back to excellence for a minute. What would be the recipe for excellence?

I think with excellence, there are always comparatives and norms. There are going to be certain practices or behaviours.

So I talk about perseverance. There’s the perseverance and the hard work day by day, but you’re working hard at the whole time that you’re countering all these people saying, you’re stupid, crazy, you should stop. This will never work. That’s really tough psychologically. Again, if you are more of a non-conformist, you may care less, right? But it still can be wearing, I’m sure.

And if you are more independent, you can care less as well.

Exactly. And I think for a lot of people was there was a real passion. They were passionate about it; they cared less what the naysayers said.

Among the people that you studied, did they follow the same steps?

I found that people either had developed an outsider independence as they were growing up or had a period of alienation. It could have been when they were in college or in their twenties — they had this kind of newcomer innocence. They had a prospective mindset from the very beginning. Now, nothing may come of that, but it’s like if you don’t plant a seed in the ground, then nothing is going to grow. So there are seeds there, and then usually what happened is there’d be a dissonant moment. It could be cognitive, emotional or existential, which then prompted the person to go into what I call discovery mode.

They had to let go of the assumptions that they had about reality. They had this openness to discovery. They were asking questions that people didn’t usually ask, and they were starting to see new possibilities. But there’s one important thing which I hadn’t mentioned earlier: everyone had to go through some sort of transformation of their self in order to discover what they were looking for.

They had to let go of the assumptions that they had about reality. They had this openness to discovery. They were asking questions that people didn’t usually ask, and they were starting to see new possibilities. But there’s one important thing: everyone had to go through some sort of transformation of their self in order to discover what they were looking for.

Kiko Thiel

This whole discovery mode is this huge complex thing. Not just this mindset of awe and wonder and curiosity, but also willing to try things to change their perspective. They were willing to change themselves. They had this compulsion to act, and that then brought them into a whole another cycle.

Once they felt this compulsion to act, these excellence behaviours of perseverance have to kick in. Otherwise someone just has an idea and they do nothing at the same time. They’re working really hard. They’re dealing with the naysayers, but they’re starting to talk to people and they start to attract people to their ideas.

And it sort of spirals up and up until you finally have enough people who believe in it, that you have created a new paradigm.

Foreign travel, or living in different countries or in different societies within your culture, came up a lot with the people I was studying, and I think it’s because they learned very early on that norms and what we think of as reality are socially constructed.

You also mentioned something that we haven’t touched based on, but you mentioned the tensions between exploitation and exploration.

In the innovation field, there’s something called ‘ambidexterity’. Exploitation is very much using your resources — sort of maximizing them. The exploration is looking for something new. That’s the innovation side. One of the big questions in the ambidexterity field is: Can an individual do both? Can an organization do both?

You’ll find that sometimes a company, rather than try to innovate, [will] go out and buy a new idea rather than develop it themselves. That’s one way of saying, “We’re going to buy it because we can’t be ambidextrous themselves”. So it is an ongoing question of can one be ambidextrous?

Once I realised that the excellence behaviours are absolutely imperative to make the extraordinary thing happen, I thought, well, one has to be ambidextrous.

Is there any other way that we can train people to set them on the path of an independent and prospection mindset? Is that something that you can cultivate with kids or with your staff members?

I was never someone who did the science that I was supposed to, and I never really went beyond that. Now as an adult I think, “Oh my goodness, the world is such an amazing place”.

I think there’s a real challenge of how one can instil this sense of wonder and have science give you the tools to discover more wonder. Children already have this sense of wonder, but [you need] to maintain it and encourage it. And by doing that you create outsider independence.

So is that something that you can translate into a company’s environment?

Part of the key is remembering that these are two different networks in the brain. If I’m managing a team, I would want to be very aware of when I want them to go into excellence mode and when I want them to go into extraordinary, because they’ve got to switch from one network to the other. So if you’re having a planning session, then have your brainstorming session at a different time or go to a different place.

You spent a couple of years doing the interviews and finishing the PhD. What were your own main takeaways after all of this exploration?

It all started with that kind of wonder and disbelief, watching the Olympic swimmer. And I have to say after all the years of working on this, I still find it really exciting. I’m finding that my research is almost like a Rorschach test. It’s like everyone takes something different. So what I’m trying to do now is talk to people, write little articles, get things out there, get people talking about this, asking about it, thinking about it, developing on it themselves. There’s so much more research we can do in so many different directions.

Additional Resources on Greatness, Excellence and Extraordinary

- What do Fine Art and Fine Wine Have in Common?

- What Makes a Classic?

- Is Fine Wine the Same as Luxury Wine?

To keep in touch with our research, analysis and events, subscribe to our newsletter.