Five Things We Learned in November 2023

Our round-up of the five most important things happening in fine wine.

November 2023 was a huge month for Areni, with the publication of our report on OIV discussions, plus our podcast on wine and health, among other activities. And then there was the heavily discounted Burgundy that caught our eye.

What does it all mean? here are our top five takeaways for the month.

1. Burgundy is not immune to gravity

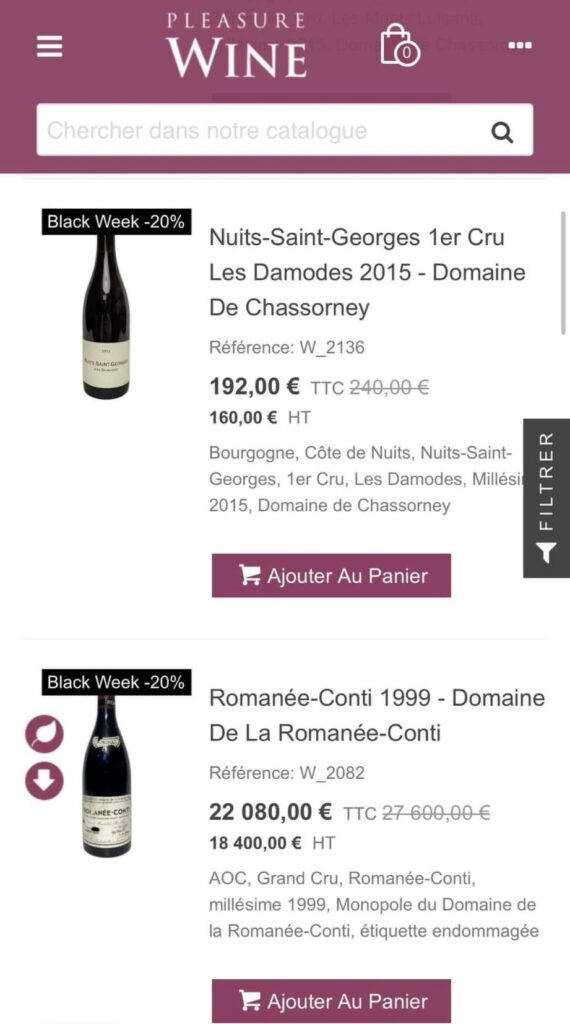

It’s hard to get shocked by Burgundy prices any more, but even we were taken aback by the offer made by Pleasure Wines, an online retailer based in Strasbourg — because we never thought we’d see these wines on sale. Although fine wine merchants re-adjust their prices regularly, they hardly discount top bottles. In late November however, Pleasure Wines ran a Black Friday deal on a number of investment grade wines, including Domaine Romanée-Conti, Comtes Lafont, and Cecile Tremblay, as well as sought-after wines from elsewhere.

It’s hard to imagine what type of consumer will leap at the chance to pay €22,080 rather than €27,600 for a bottle of DRC; anyone who can afford to pay five-digit sums for a single bottle of wine is probably neither price sensitive, nor motivated by discounts. But the mere fact that these wines were being discounted points to a new reality — even the top end isn’t immune from the economic forces rippling through the wine world.

Areni has been told privately by industry watchers that there will probably be a market shakeout in the coming months, as the luxury sector finally cools. This is what we’ve heard:

- Classic and super iconic wines that currently maintain a market-leading position will continue to do so, and will probably hold their prices. But this only applies to 15 or so Burgundy producers, the Bordeaux First Growths and a few Californian wines such as Harlan Estate and Screaming Eagle.

- Wines that sit below these icons may see their prices fall.

- Anything of average quality that has been riding the price waves in recent years — think many of the Burgundy villages — must adjust their prices, or see their sales evaporate.

- There will, however, be winners: the wines that stayed affordable while delivering great quality, such as wines from Tuscany and Piedmont.

For anybody who is still hoping to see their wines achieve investment grade status, the message is clear: you will need to be on the road, hand-selling your wines. And stay realistic about prices, because it’s better to be underpriced for the quality than overpriced. A lot of fine wine is about to become affordable, so the competition will be fierce.

2. You need a disaster preparation plan

Somehow, November has become international conference season, with major wine conferences being held from California to Verona to Adelaide. One of the most interesting talks of the season was done by Hamish Saxton, CEO of Hawke’s Bay Tourism, speaking at the Wine Industry IMPACT Conference, held in Adelaide in the last week of November.

Hawke’s Bay is New Zealand’s second-largest wine region, and the biggest producer of premium Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. It’s also a fruit and vegetable region, making it a magnet for visitors interested in gourmet experiences. By 2020, visitors were spending NZ$696m (€397m) in the region; 80% of the visitors were local, but there were a growing number of internationals as well.

“We were coming out of Covid recovery pretty strongly, with a record cruise season underway, and a great deal of beautiful digital and marketing content related to food and wine country,” said Saxton.

Then, disaster. On Valentine’s Day 2023, Cyclone Gabrielle arrived early in the morning, bringing flood waters and huge silt deposits, and knocking out all power. Bank machines ceased working and phone towers collapsed.

“We all had to largely fend for ourselves. There was an information vacuum,” said Saxton. “Visitors could only fly out, as road was not an option. Hotels began to shut down, unable to provide lighting, catering, and laundry. The city’s sewerage management system went down.”

With no power, the only way to communicate was through pen, paper and meeting people in person.

There was a lot for the authorities to take care of: there were stranded people to take care of, and plenty of silt to be shoveled, but taking charge of the communications flow also became an urgent priority. National agencies needed to let the world know that the disaster was confined to Hawke’s Bay, so as not to damage the rest of New Zealand’s national tourism economy; however, they were relying on the limited information coming out of Hawke’s Bay, and often got things wrong.

Saxon’s group created a war room and established their priorities, including mapping which businesses were opened, closed or operational; mapping the situation with infrastructure, particularly water, power, roads and the airport; providing emotional support; and taking care of prosaic matters like refunds. They “activated the network”, keeping everyone from hotel operators to local politicians up to date. Within a week, around 85% of the tourism businesses were operational again.

Not surprisingly, given the scale of the disaster, there were many major and unexpected challenges. First and foremost were the massive number of cancellations. But the continuous disaster coverage also hurt the region, as did visits by celebrities whose real purpose was to build their own profile, rather than help the community.

Saxton’s takeaways are that disseminating good information is critical, as rumours swirl in a disaster — it’s important to “own the narrative”. They launched a “Live from Hawke’s Bay” campaign on social media, producing daily videos of people in the region — 59 per day. Another key plank was keeping locals up to date on everything that was being done. And they created a set of public milestones, to demonstrate how well they were recovering.

“The amount of work you need to do depends on your reputation in the first place, and the degree to which you’ve been affected,” finished Saxton. He listed the things that need to be done: fundraising, PR and marketing, network management, “combating ‘other’ noise” and getting out with shovels. “And you need to manage the narrative, be real, be solutions-focused, remain indispensable, communicate well and as often as is required, and don’t waste a crisis — its good practice!”

As he added, “normality is the period of lull between calamities” — especially in an era of climate change — so everybody needs to be prepared for when the worst happens.

3. The spaghetti bowl effect

In October, the team from Areni went to Dijon to hear the Organisation of Vines and Wines (OIV) thrash out the issue of non-tariff trade measures (NTMs). Over the course of a long and involved day, many acronyms were used, from non-tariff trade barriers (NTBs) to the Spaghetti Bowl Effect.

Here is what we learned:

Sometimes countries slap tariffs (customs duties) on goods, to protect the local market, or to further political goals. An example would be China imposing a 218% tariff on Australian wine in March 2021, which immediately killed Australian wine exports to China. This was widely seen as retaliation for a diplomatic dispute between the two countries.

But sometimes it’s possible to create trade barriers without the use of tariffs.

There are NTMs, for example, which are policy decisions that can affect trade. These “technical” measures include things like plant quarantine requirements, certifications, labelling requirements, and other regulatory issues. While these can erect barriers to trade, they are also legitimate uses of policy. Certifications can ensure high safety standards, for example.

There are also non-tariff barriers (NTBs), which countries use to restrict trade. These can include quotas, embargos or sanctions. And then there’s the Spaghetti Bowl Effect, which is what happens when countries organise Free Trade Agreements between themselves, that in practice override World Trade Organisation agreements.

Fortunately for the wine trade worldwide, the OIV exists to try and harmonise wine legislation between countries, to try and reduce trade barriers where possible.

Areni wrote a report of the day, which members can access here.

4. Wine labelling doesn’t work

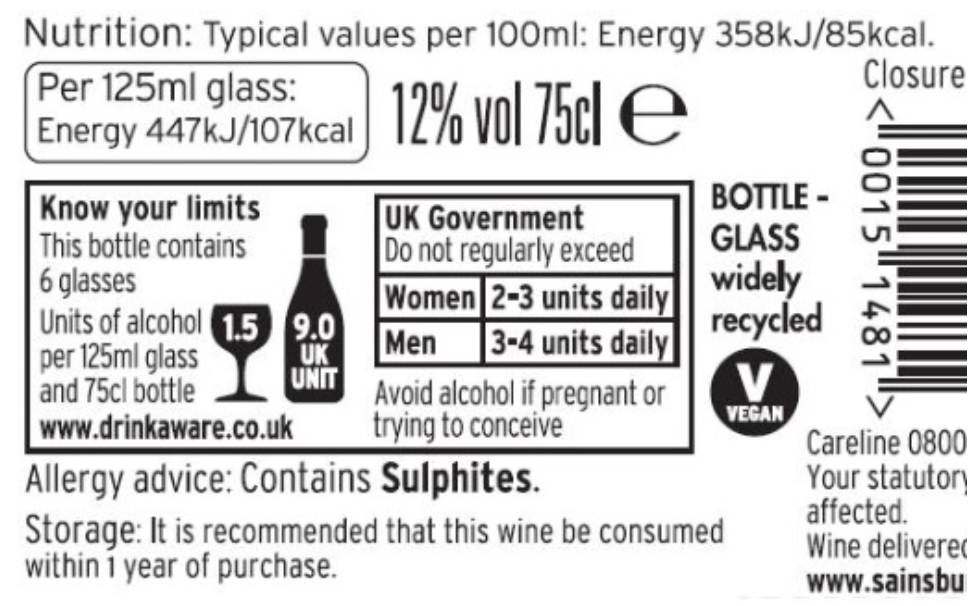

On 8th December 2023, all wines sold inside the European Union will need to bear a nutrition and ingredients label. Consumers will finally know for sure how many calories lurk in that bottle, and whether or not preservatives have been used in the wine.

Prior to the new regulation, there have been years of discussion within the wine trade, some of it acrimonious, on the topic of ingredients. What’s an ingredient — and how does it differ from a processing aid? Should consumers have the right to know that PVPP was used to reduce the colour of this rosé, or Velcorin was used to kill bacteria in that wine?

The new requirement doesn’t go far enough for some wine people, and it goes too far for others.

It turns out none of this might matter. According to Pierre Chandon, Professor of Marketing, Innovation and Creativity at INSEAD, governments have long used food labelling as a way to encourage consumers to make healthier choices. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work.

“It works for people who are already healthy, who care about health and nutrition, but it doesn’t really move the needle for the majority of people,” he told Areni, “because when people choose what to eat or drink, they focus number one on taste.”

He added that he was surprised by the disconnect between the effect of these labels on consumer behaviour, “which is not that big, and the effect on marketers, who are really scared by them and are going to reformulate their food and really lobby intensely against them, even though in reality they don’t change people’s behaviours that much.”

So the new wine labels may do exactly nothing, except create more work for most producers. Still, it’s always good to be transparent — and labels will be a boon to the most engaged wine lovers.

You can hear the whole discussion with Pierre Chandon here.

5. Wine and health don’t mix

Japan is the latest country to revise its drinking guidelines downwards, in what is becoming an international crackdown on alcohol consumption in the name of health.

In late October, a congress on wine and health — the Lifestyle, Diet, Wine & Health Congress — was held in Toledo, Spain. It brought doctors and scientists together to look at the evidence that wine has health benefits or, at worst, that it doesn’t cause harm.

As Areni’s editorial director Felicity Carter discovered, however, the evidence is complex: the regular consumption of moderate levels of wine has a positive impact on the cardiovascular health of the over 40s, but a negligible one on younger drinkers. In moderate amounts it’s unlikely to cause cancer, but it’s not recommended for women who have a family history of breast cancer.

Above all, wine is best consumed alongside the Mediterranean diet.

This means it will be hard for the wine trade to push back against ever tighter drinking guidelines, because it’s much easier for governments to say “no safe level” than it is to unravel the complexities of the impact of moderate wine consumption on human health.

All these issues were discussed at length in one of our most popular podcasts of the year, The Responsibilities Series Episode 2, Wine & Health, which you can hear here.

To keep in touch with our research, analysis and events, subscribe to our newsletter.