Biodiversity, Fire and Catastrophe: A Discussion with Bill Harlan and Richard Mendelson

Today, Bill Harlan is one of the legends of Napa Valley, whose Harlan Estate wines have a cult following. He was also the founder of Bond and Promontory, all of which he recently placed under the leadership of his son Will.

In his 30s, Bill and a partner created a property development company, the Pacific Union Land Company, which ultimately was involved in handling billions of dollars of real estate primarily in California. One of his earlier developments was the five-star Meadowood Resort in St. Helena, which was a modest country club when he bought it in 1979. It became the home of the glamorous Napa Valley Wine Auction, which for many years was the highlight of the Californian wine calendar.

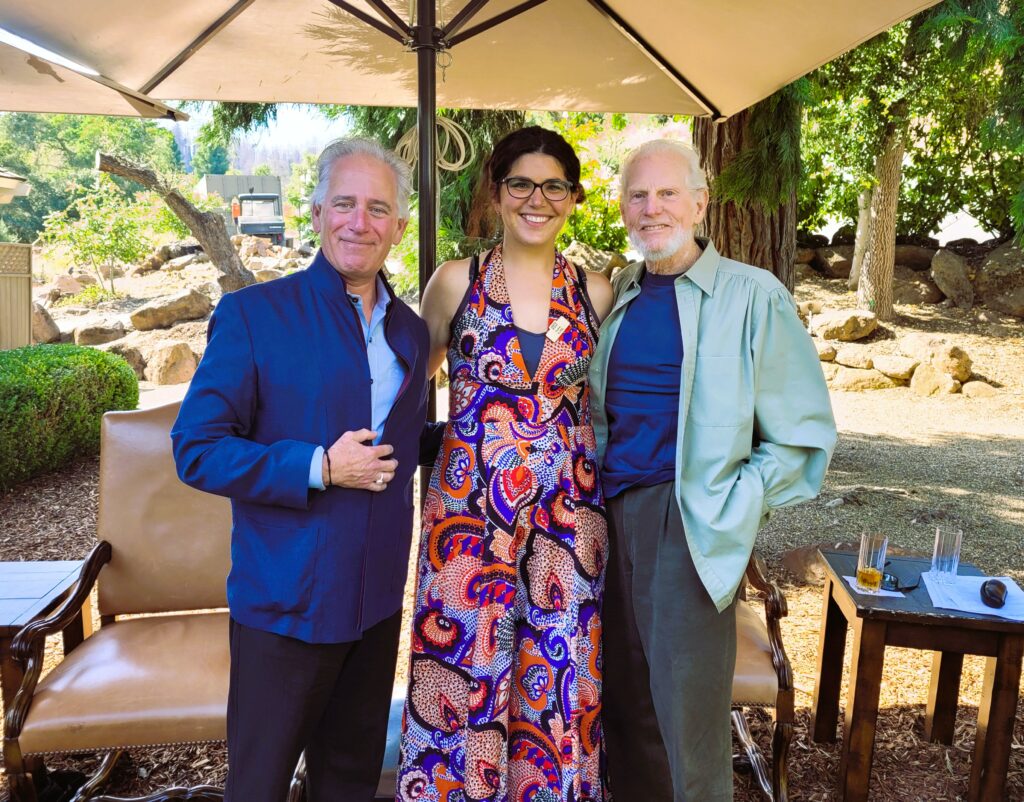

Then, in September 2020, the Glass Fire swept through the resort, leaving destruction in its wake. When Areni Live went to California in June this year, Areni CEO Pauline Vicard sat down with Bill Harlan and renowned wine lawyer and industry expert Richard Mendelson to talk about history, biodiversity, fire management and staying resilient in the face of catastrophe.

Pauline Vicard

Tell us about the origins of Meadowood and your initial vision of the place.

Bill Harlan

When I was in school, one of the things I heard was you could go up to this place called the Napa Valley and you could go wine tasting. They don’t check your ID, the girls like going up there and it’s free. And so I said, as a college student, “We’ve got to at least go up and see this place”. That was the beginning. I came back a year later, 1959. It was so beautiful. And at that time I said, “Someday if I could ever afford it, I’d like to buy a little piece of land and plant a vineyard”.

That took me about 20 years. So it wasn’t until ’79 that I acquired my first piece of property here, where Meadowood is now. It didn’t look anything like this. When I first came up here in the ’50s, Napa Valley and Silicon Valley looked about the same. And now you look at it 60 some years later and the Napa Valley is still in agriculture and Silicon Valley looks like a lot more of San Jose and the rest of California in an urban setting.

That’s what inspired me to make a bigger commitment. I saw the property here on a Sunday afternoon, and by 5:00 a.m. on Tuesday, less than 48 hours, I owned it. It was going to a foreclosure sale, and it had been for sale for two years. I couldn’t figure out why no one else had bought it. It looked so good to me, I couldn’t resist. I could barely afford it. Now, I had no idea what I was going to do with it.

I got a call from Mr Robert Mondavi. When you get a call from Mr Mondavi, you take it. And he invited me to lunch. So I went to lunch. He asked me why I bought this property, and I told him my dream that I’d like to plant a vineyard, find a wife, raise a family, and make wine. And he said, “Well Bill, that’s an interesting idea, but the Napa Valley has much more potential than that, and I think there are some other things that might be more interesting”. And I said, “Why did you invite me to lunch?” He says, “Well, that property you bought, I think it could be a great place for the community, which has kind of been a little club for us and a place for when visitors come”. There were seven little cabins as well as a clubhouse, a restaurant, some tennis courts, a 9-hole golf course and a swimming pool. That was about all that was here.

He said that Napa Valley has way more potential than this. “And what I’d like to do is a wine auction.” I had no idea what a wine auction was. Had never even heard of one. And so I said, “How does that make any economic sense or anything?” He says, “Well, you’ve got to think beyond that”. And he said, “What I’d like to do is give you some perspective. I would like to set up a trip for you to go to Bordeaux and Burgundy and see what these properties are like. And at the end of the trip, there’s a wine auction that goes on by the name of the Hospice de Beaune”.

I took him up on it, went on this three-week trip, and it was life changing. Seeing this changed my whole perspective on time as far as building things for generations. I came back and said, “I’m willing to help. What are the primary goals here?”

He said, “There are two main things we want to do.”

“We want to try to help put the Napa Valley on the map. We have the potential of producing wines here in the Napa Valley that would be welcome at the table of the fine wines of the Old World. And the other is to raise money for the community. And with this wine auction, we could do both.”

And I said, “I want to get behind this idea”.

It’s hard to believe that you could do something like the Hospice here. At that time, there were maybe between 20 and 30 wineries, and only about five of them you could visit. It was a very quiet, sleepy place. Anyway, that’s how it started ,and that was the idea. The first wine auction took place here in 1981.

Pauline Vicard

If we move now to the events of 2020 and the Glass Fire of September 2020, can you tell us a bit what happened then? Very shortly after the fire, you said this should be an opportunity to not only rebuild, but also to rebuild something better.

Bill Harlan

From 1979, I remember the number ‘35’ really clearly. Our occupancy rate was 35% and our room rate was $35 a night to give you some idea of how much business there was in Napa Valley and what people were willing to pay. And so, we built Meadowood for the market at that time. That was now over 40 years ago.

We were among the best up here at that time. But as time has gone on, we now look back at the forest fire and say, well, it’s somewhat of a blessing in disguise. We would never be able to do what we have the opportunity to do now, which is almost start with a clean slate and build what is right for the market for the next 40 years. So that’s our challenge, and that’s our opportunity.

[In 1979]Our occupancy rate was 35% and our room rate was $35 a night to give you some idea of how much business there was in Napa Valley and what people were willing to pay. And so, we built Meadowood for the market at that time.

Bill Harlan

From the time we started, say with the wine auction and getting the approvals to build what we built originally, we’ve gone from say 25 wineries to over five-, six- or seven-hundred wineries. So the place is so different today, plus you’ll find Napa Valley wines around the world. There were very, very few wines from the Napa Valley around the world in the beginning, and now the Napa Valley is beginning to be known globally.

Pauline Vicard

Richard, a question for you. When we prepared this conversation together, you said that we needed to go from a fire-suppression model to a resilience model. What does it take to go from one model to the other?

Richard Mendelson

Well, we’ve had the fire suppression model in California since statehood in 1850. The idea was you extinguish a fire. The use of fire for prescribed burns or controlled burns, or what used to be called the ‘cultural use of fire’, was banned. So we’ve had a model that puts out fire but doesn’t deal with vegetation management. There was an ethos in the county that you couldn’t do any earth moving or vegetation clearing without a permit, except on flat ground. I remember being asked by so many wine industry persons, “Can we take down a tree? We need to clear out the vegetation”.

The answer was, ”I don’t know”. There may be someone with a drone flying overhead who’s going to find out what you’re doing. Frankly, it was the wrong approach. And that’s changed as a result of the fires. And now we have a model of fire prevention and doing what’s necessary. Bill has been a leader at Harlan Estate and the other wineries of the domain in actually doing what’s necessary to mitigate fire risk, working with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire) and Napa Firewise.

Pauline Vicard

Do you need to plant species that are more resilient to fire or more prone to stopping it?

Richard Mendelson

Well, the relationship between biodiversity and fire is an interesting topic. Obviously, fire destroys plant and animal life, so you think of it as destructive but I’d say it’s a disruptor; you can plant new plants, and the wildlife population changes. In some sense, it’s an opportunity. It’s interesting to me that Cal Fire is now consulting with tribal leaders on prescribed burn and other techniques that were used by indigenous people. In terms of farmers, we’re very interested in vineyards as shaded fuel breaks, particularly on ridge tops.

Grapevines are very resilient and do not burn easily. So if a vineyard is strategically placed, it can slow down a fire, and it can also be a staging point for firefighters to go in and fight the fire. Our fire mitigation techniques include the strategic use of vineyards as shaded fuel breaks, the management of the vegetation cover crop, reducing the fuel load in the forest, and removing the ladder fuels that’ll lead to a canopy fire.

Our fire mitigation techniques include the strategic use of vineyards as shaded fuel breaks, the management of the vegetation cover crop, reducing the fuel load in the forest, and removing the ladder fuels that’ll lead to a canopy fire.

Richard Mendelson

Bill, you jump in please. You’ve been very involved in this.

Bill Harlan

It’s something we have been doing now, I’d say between 25 and 30 years. It was very, very difficult to do it because it was against the law to even take a tree down. They didn’t want to see any buildings that were in the hills. And so it was a combination of the environmentalists [saying] not to touch the forest and the people living on the floor of the valley and the cities who didn’t want to see anything in the hills.

And if you lived in the hills, it was virtually against the law to do anything. It was impossible to protect your home or protect really anything. And if you planted a vineyard, you really couldn’t touch anything near the vineyard. A hot enough fire can come in and destroy the perimeter of your vineyard anyway. And the smoke from it ruins the crops. And so it makes it very, very difficult.

Pauline Vicard

You’ve both mentioned regulation and the politics that come with it. Sometimes there’s a real battle between environmentalists and the farmers. When you are in that situation, what can we do?

Richard Mendelson

The fires changed the dialogue. People realised that we needed to do something. There was a more robust dialogue about forestry management and farming techniques and cover crops, which are obviously good for biodiversity. I think what’s happened in Napa County is that people are more willing to have an open discussion.

Pauline Vicard

You’ve been studying nature and the resilience within the woodland trees and the forest here at Meadowood for the best part of 40 years. Can you tell us a bit about the research that you do?

Bill Harlan

We worked on it mostly with the universities, with the people that really know what you have to do to manage the forest. So we’d take forest rangers out there. We walk through the forest and ask them how can we best manage this? And they start out by saying every acre of land can only keep a certain amount of healthy trees over the long term.

When I came from that trip in 1980, I put together a plan, a 200-year plan of building something that could last for many generations. And so if we’re looking to create something and take care of it, sustainability is something we have to have. We don’t want forest fire. We want the land to be as healthy as possible.

We have the mountain lions, we have the bears, we have the foxes, we have the deer, we have all the wild animals all around. Only 10% of our land is planted to vineyards, and the rest is woodlands and wildlands and forest. We have to manage that the best we can. They won’t let us bring in fire breaks, they won’t let us bring in roads, they won’t let us do the things you have to be able to do to manage the forest land.

But what’s happened here since the fires that Richard’s talking about, is the insurance companies are moving out. So the two most important insurance companies here in California have been Chubb and AIG. They left us about a year ago. It’s very difficult to get insurance. We’re trying to figure out all the rules, so we can get in and take care of the forest and be able to protect our buildings and vineyards; they’ve increased our rates another 33% or 36%. Nobody can afford the insurance rates that we’re paying right now.

But what’s happened here since the fires […], is the insurance companies are moving out. So the two most important insurance companies […] left us about a year ago. […] They’ve increased our rates another 33% or 36%. Nobody can afford the insurance rates that we’re paying right now.

Bill Harlan

We’re going to have a lot more pressure from insurance companies. People can’t get insurance on their homes. You’re getting pressure from the banks. The banks will recall their loans if you can’t get insurance on your assets.

Richard Mendelson

Just to add to that, there are wineries in the Napa Valley that can’t get insurance. Many [winery sales] fall apart because the buyer can’t get insurance. And so the state stepped in and established a state-mandated consortium of insurers offering what’s called the California Fair Plan, which is the insurer of last resort. It’s very expensive and it’s not very good coverage.

Pauline Vicard

If I try to summarize, one of the main lessons that you’ve learned from the fire, for example, is the way we need to adapt forestry management. You have to remove the fuel, but you don’t want to create a new imbalance.

Bill Harlan

That’s right. But that takes someone with knowledge. We can learn it from the universities, learn it from the scientists, the people who study it.

Richard Mendelson

You need to assemble a team — registered professional foresters, pedologists (soil scientists), ecologists —who understand it’s an ecosystem. You’ve got to understand all the aspects of it to have it function properly.

Bill Harlan

We’ve been putting that together. We know that it’s the ladder fuel that really gets the fires going, and that you have to separate the trees and separate the canopy. Once you have canopy fires going, you can’t put them out from on the ground. You have to wait for the fire to burn out.

You can see where the hills are all black. The fire had gone through the year before, and it’s now been 15 years and that hill is not black anymore, but there’s nothing on it yet. It’ll take another few generations — two to three generations — before it gets back to looking good, let alone all the flora and the fauna coming back. It takes a handful of generations to get it back again.

But to effectively manage the forest is very, very costly. It costs as much as it does to buy the land to start with.

Now people are starting to realize that if we don’t do something about it — and if a lot more people don’t do something about forest management—it’s going to be a bigger problem. We don’t have nearly as much resistance to this viewpoint here in the last few years : all of a sudden, more and more people have started to tune in.

This conversation has been taken from a wide-ranging discussion that involved multiple people. It has been edited for length and clarity.