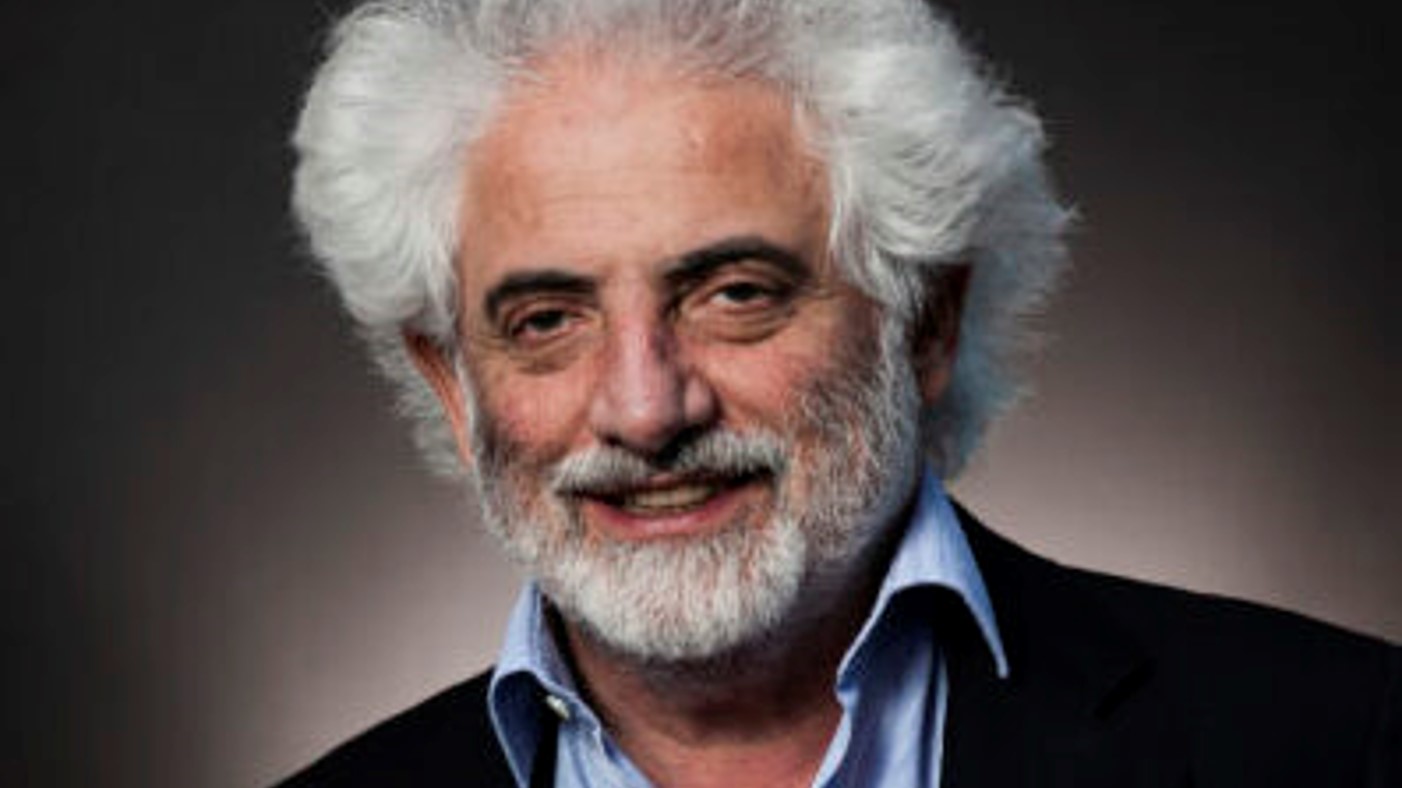

The Evolution of Fine Wine, And What Lies Ahead, by Michael Fridjhon

Michael Fridjhon is South Africa’s most highly regarded international wine judge, the country’s most widely consulted liquor industry authority, and one of South Africa’s leading wine writers.

On July 12th 2022, he delivered the following speech for the opening of ARENI annual’s think tank in Stellenbosch, South Africa.

“When you get invited to deliver a speech where the briefing note asks you to reflect on how you’ve seen the world of fine wine evolving, you know that you’ve received a coded message about your age, a message which implies that you have seen the world evolve from the days when Falernian was the wine of choice for the dinner at Tremalchio’s.

Happily I haven’t taken this to heart: the fact that I have been drinking fine wine – truly fine wine – for over fifty years is a combination of several factors: a very early and precocious start, the good fortune of growing up in an environment in which my parents and their friends served really good wine frequently – and children were allowed to sample what was on offer, and perhaps, most importantly, that the great wines of that era were accessibly priced.

When I was still at school I picked up a second hand copy of Andre Simon’s Tables of Content – the menus and wines served over a 5 year period between 1929 and 1934. When “Lunch at the Office” is a bottle of 1865 Chateau Margaux served with an omelette, followed by an 1858 Lafite to accompany the cheese, you immediately get a sense of the envy I experienced at having been born a generation too late.

That might of course be true of every generation: the primeur prices of the first growths from great late 1920s vintages were only a few shillings a bottle – but then we have to remind ourselves that they came to market in the midst of the great depression. It doesn’t matter how inexpensive they may seem to us today. The question is always one of affordability.

Or is it? What if the game has changed in a way which makes comparisons impossible: let me give you an example. In the 1930s the Domaine de la Romanee Conti had bottles of their wines in baskets inside the entrance hallway to their offices. We would call them dump bins today, and they were an important point of retail for the domaine – which, while it already enjoyed an unparalleled reputation, was still battling to sell its wines.

I have a 1971 price list from one of the wine merchants I patronised as a student. A bottle of 1966 Romanee-Conti sold for R18-50 and the infinitely better 1964 for R19-00. A 1945 Clos des Lambrays was R8-50. The same price list shows that the best known Cape wines were R1-20 and R1-30 respectively. That would imply that the exchange value of 1945 Clos des Lambrays was 7 bottles of 1967 Nederburg Selected Cabernet – and which in turn shows that, even then, it was more difficult to sell the “unknown” imported wines than the well-branded (and very well made) local champions.

No – it is quite clear that there has been a dramatic change in how the high-end of the market has evolved. It has moved from surplus to shortage in a few decades – this is a key consideration – so that with this shift in interest and demand, the world of wine has been irrevocably transformed.

It is quite clear that there has been a dramatic change in how the high-end of the market has evolved. It has moved from surplus to shortage in a few decades – this is a key consideration – so that with this shift in interest and demand, the world of wine has been irrevocably transformed.

We attribute to Steven Spurrier’s Judgement of Paris tasting the coming of age of the American wine industry. No doubt it played a role, if only because it must have contributed to Americans beginning to take their own wines seriously and in turn helped to make American wine a beneficiary of a process which was happening all over the world in the crucial decades which followed the wine market collapse of the early 1970s – a time when I imported Chateau Petrus for R9-00 per bottle landed in South Africa.

As the market recovered – after the battering of the 1973 war, stagflation, and the massive hike in petrol prices (does this sound familiar), Robert Parker devised a way of guiding well-heeled Americans in their purchases of fine wine. To be clear, this was wine which brought with it the prospect of delivering social prestige. For this reason alone, it acquired a vastly bigger market than it had enjoyed as the beverage of choice of the old world elites.

The same process happened in South Africa, driven for similar reasons. In the early 1970s the very best South African wines sold for less than R1-50 per bottle. Then suddenly the wine of origin legislation (which became law in 1973) compelled producers to be at least a little honest about the salient information conveyed on wine labels. Instantly there was a great red wine shortage, and prices of the most desired wines trebled within a few months. Out of the blue, the mere possession of a bottle believed to be unobtainable imbued the owner with a stature previously only acquired as a result of having a luxury car or an expensive mistress.

So if what has transformed good wine into a luxury has been little more than a shift from surplus to shortage, and the ensuing change in perspective, how safe is its status today, when many of the elements which led to the market crash of the early 1970s are again upon us? Is there really a way of defining what it is (rather than its USP) – and which exists independently of its commercial desirability? Can the genie which has turned so much – sometimes quite ordinary – vineyard into something unimaginably valuable within a few decades be squeezed back into the bottle?

Where would we be if the market contracted to the levels of the 1970s – or the 1980s or even the 1990s? Have we confused the concept of fine wine with the concept of an object of luxury? Is the mere fact that the best known premium wines have become an investible commodity actually served the interests of fine wine?

These are some of the questions I am sure we will be addressing over the next few days, so it would be pre-emptive and unwise for me to attempt to answer them. However, there are some ways where a glimpse of what has happened to the premium end of the Cape wine industry since the advent of democracy in this country may illuminate the discussion, and may justify treading – a little cautiously – into this territory.

A few decades ago we had no more than half a dozen properties contesting for a place at the pinnacle of the industry. Several were quite new, but in long established appellations, and run by people whose credibility could never have been in dispute. Mostly they sold their best wines for less than R100. Almost all of them still occupy a spot high up the pyramid. Perhaps two of them have achieved that balance where their volumes are significant and their retail prices sit at R500 or more – so that they are prestigious and profitable, and not making their money by selling putative shortage.

But we have many others which sell smaller volumes for the same or less, and a few which sell smaller volumes for significantly more. In that sense there is a healthier spread, one which makes possible the growth and evolution of an industry which was 20 – 30 years behind the rest of the world by the time we emerged from the era of isolation.

We need to understand the very impermanence of this, especially in the context of the New World. Unlike the Old World where origin imbues a wine with stature even before the grapes have reached the press, the New World offers great mobility – but at the risk that you can go from hero to zero in a season. It therefore encourages a culture where to succeed (at least in the short term) a wine has to make an impression: size, weight, textural polish, showiness – if you like – trump nuance, finesse, intricacy and savouriness. And since I think that qualities like complexity, finesse, weightless rather than absent tannins, intensity without visible force, are the hallmarks of fine wine I seriously doubt that many of the high-fliers of today will find themselves in my fine wine pantheon.

But this is also what makes the future of fine wine so exciting. More and more sites with extraordinary potential have been discovered, or resurrected or emerged because of climate change. Together with the worldwide growth in interest in fine wine, and the accepted mobility of place and opportunity which the past half century has delivered, we now have a unique dynamic driving change.

So we sit at the cusp of another new world and its new fine wines. Some of the consumers who were seduced by form, not substance, will redefine their expectations. Producers who tire of pandering to the tastes of those who treat fine wine as a means to an end will discover or revive these special sites. The market – that is to say, the consumers and what they consume – will undergo another transformation.

Yes, there will be mistakes, roads which lead nowhere, paths that lead to dead-ends, but there will also be an asymptotic ride towards a sense of perfection which has always been part of the world of fine wine. Hopefully this will meet the needs of what we must believe will be a growing market by increasing the supply of what is really fine, and truly satisfying.”