ARENI Live Insights: The Current State of Global Trade

Picture Kurt Cotaoga on Unsplash

ARENI Live is a multi-day event combining panel conversations, roundtable discussions, and collective intelligence workshops. By invitation only, ARENI Live brings together critical thinkers, from iconic and forward-thinking fine wine producers, to leading academics and business leaders. This year, ARENI Live was held in Stellenbosch in July 2022.

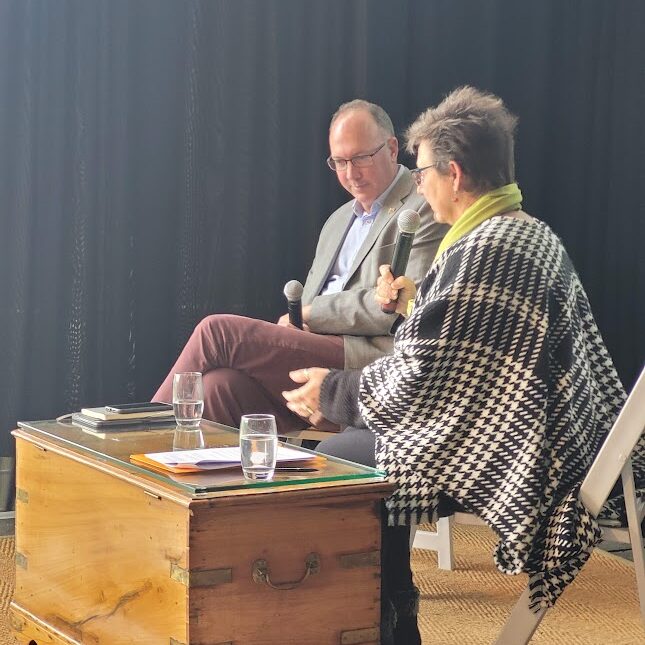

Among the topics discussed was financial sustainability and global trade. As part of those discussions, South African wine expert Cathy van Zyl MW interviewed His Excellency Antony Phillipson, Her Majesty’s British High Commissioner to the Republic of South Africa. He took up his appointment during July 2021. A career diplomat, HE Phillipson joined the Civil Service in 1993 and has held a number of posts in the UK Government.

Cathy van Zyl MW

How have the changes over the last five or ten years affected Her Majesty’s government’s trade policies? And what does that mean for historic trading partners like South Africa?

HE Antony Phillipson

There’s a lot in there and a lot of directions we could take but let me give you three thoughts. First of all, if we look back to pre-COVID, probably the biggest impact on whether you want to call it a realignment or a reassessment of the UK’s trading relationships with the outside world, came as a result of the decision to leave the European union. And 23rd June, 2016 began the process of Brexit that eventually culminated in formal legal terms at the end of January 2020.

At one level, there is no difference for South Africa’s engagement with the UK inside or outside the EU. What we tend to hear from some South African partners is that some of the things that they might have hoped the UK would argue against from the trade policymaking table in Brussels are now more likely to happen because we are not there.

So Brexit was the big one, and then COVID was the next one. You know, when it hit, I was sitting in New York. I was doing a job that was fundamentally engaged in our trade policy with the US and Canada. So we would talk a lot to people about what the impact of the COVID economic shock was. And it was certainly different compared to the global financial crisis in 2008, 2009, 2010, some of the consequences of which we’re still living with, because it was almost a tap turning off economic activity. And then as we came out of it, you turn the tap back on again.

The problem is, is that it did fundamental things in some parts of our economy, including some of the things we’re still wrestling with now. In terms of the travel sector, anyone who has the misfortune to go through Heathrow, or indeed, probably any number of other international airports over the next few months is going to have a real problem because people were let go despite the furlough schemes that we put in place to try and keep people employed. And so we will be living with the consequences of that, on top of the consequences of the UK leaving the EU, and then the conflict in Ukraine and the impact that is having on global food prices, which are having massive effects across the whole of Africa, but are also driving up the cost of things like fuel in places like the UK.

It is now I think, £2 for a litre of unleaded petrol. If you told me that two years ago, I would’ve been horrified. It’s 26 Rand for a litre of unleaded petrol here in South Africa. And a year ago it was 16 Rand. You layer those economic shocks on top of each other. They all have different origins. They have different ways that they’re going to play out, but I fear they’re going to continue to interact with each other in a way that creates just a more severe economic context for us all to live in.

The question is whether the global community can come together, as we did after the global financial crisis through the G20, I would argue largely under the leadership of then (UK) Prime Minister Gordon Brown; and whether we can find ways for the EU, the US China, the UK, Japan, and indeed leading players in Africa, like South Africa, to work together in those global organisations.

I’m not optimistic for one reason, which is that again, if you look at something like the World Trade Organisation, largely as a result of US trade policy and not just under President Trump, the WTO was already starting to have a problem in terms of settling disputes, because the US wouldn’t approve any more judges to the dispute settlement body. The WTO was also having problems making new trade rules because of differences between China and India and the developed world when it came to things like future market access agreements. We’ve just had a bit of a breakthrough in the WTO with a breakthrough agreement on fishing subsidies, but that’s taken, I think, about 10 years. The idea that soon we’re going to have any kind of meaningful services liberalization, which I think is fundamentally important to an economy like the UK and probably also the most of the rest of the EU—you know, a meaningful eCommerce agreement, a meaningful international technology agreement, a meaningful financial services agreement—those are still slightly elusive, and yet those are the issues we’re going to have to think about if we’re going to understand, mitigate and then recover from the impact of Brexit.

The idea that soon we’re going to have any kind of […] meaningful eCommerce agreement, a meaningful international technology agreement, a meaningful financial services agreement—those are still slightly elusive, and yet those are the issues we’re going to have to think about if we’re going to understand, mitigate and then recover from the impact of Brexit.

HE Antony Phillipson

Cathy van Zyl MW

Bringing it now to the world of wine, do you see those challenges that you’ve just outlined impacting the fine wine trade? Or do you see the fine wine trade facing other challenges in the years ahead?

HE Antony Phillipson

I think we may need more wine in the years ahead [laugh]. A couple of thoughts. It feels to me that the wine trade—whether the fine wine end of it or down the more household end—there are things that you need. You need supply, demand and access. So by supply, I mean really going back to what I was saying earlier. What is climate change going to do where traditionally wine has been produced? It will actually create some opportunities, including in places like south of the UK, which is producing wine.

You need to think about how you’re going to supply fine wine. And I’m sure all of you in this room think about that day in and day out in terms of demand. I think there’s a question about how you bring your products to market, how you advertise, how you build your brands. How do people find out about your wine? How do people then get hold of your wine when they find out about it? As I’ve said to a couple of people here today, we are encouraged as British diplomats to promote UK food and drink, which I’m very happy to do when it comes to things like Welsh cheese or Scotch whiskey or gin.

I find it a bit more complicated when it comes to English wine, because although I think there are some fine English wines, especially sparkling wines, they’re not very readily available here.

Then, when I come to access, there’s two things. First of all, what are the market access barriers that you bump into? I recall that when the UK, as part of the EU, we were pushing for conclusion of a meaningful free trade agreement between South Africa and the EU. I think the last remaining bit of the jigsaw to drop into place was a wines and spirits agreement, because there are quite a lot of European producers of wine who didn’t want the untrammeled competition of South African wine.

And we’ve gone through that journey with Australia, with New Zealand, including after Brexit, as we negotiate our own trade agreements with those countries. So tariffs matter because they make quite a big difference to the price of a bottle. Maybe not at the fine wine end. Maybe your consumers are able to adjust to that, but certainly down at the household end, it matters to people whether they’re paying £8 for a bottle of wine or £6, and then the other thing about access. And I certainly used to feel this quite keenly when I was in the US is that unfortunately people seem quite keen to reach for the alcohol industry when they’re thinking about how to apply tariff barriers to other countries as part of trade disputes. I don’t remember wine being a big issue between the US and the EU as we argued over steel, as we argued over aircraft. But certainly spirits was always quite close to the top of that list.

So there’s a problem there, which is that you end up being caught up in trade disputes that are nothing to do with you and not of your making, but because you are local producers.

Cathy van Zyl MW

For some of us, we see the movement by the World Health Organization to try and get governments to install more risk messaging on wine, as quite a big risk. What is your advice for a product that is highly dependent on export markets in a world that appears to be leaning towards fragmentation while penalizing it on all fronts? I mean, we’ve got taxes due to tariffs, alcohol bans, threats of prohibitions, climate change, potentially climate change taxes that are coming in. Where do you think we can go?

HE Antony Phillipson

You know, I still think you are fundamentally different to the tobacco industry, but maybe it feels from your side of it as if you’re getting closer to that world. I think the answer in terms of market access issues, export market issues, is to do what I personally have always been very committed to doing myself, which is a dialogue between those who make policy, whether at a national level or an international level, and those who are the producers.

I think in the UK, we’ve tried very hard to have that dialogue between the private sector and government. Because then when we sit around the table in the various organizations I’ve mentioned, we should have top of mind, what are the issues that are driving economic opportunity in our countries. And I certainly think between UK and South Africa, the alcohol industry is a fundamentally important part of both economies. So we should be talking to each other about what type of discussion we want to have to address those issues. I think governments are always going to wrestle with—and I say this is a civil servant who advises and supports a government rather than as a politician within one—governments are always going to feel the pressure to regulate, feel the pressure to respond to consumer demands.

And some of those demands will be for less taxation, less alcohol duty, more permissive regimes, and some will be in the other direction. I think governments will always look to try and maintain that balance. Someone once said to me that as well as people reaching for the alcohol industry when it’s time to apply retaliatory tariffs against another country, domestic governments sometimes feel a bit quick to reach for alcohol duty when it comes to repairing things like public finances. And certainly I think for the UK and other developed economies, we are going to be looking at how we deal with the impact on public finances of COVID, and other public pressures for some time to come. And I guess that will mean that whenever we approach budget day in the UK, people will be watching to see what the chancellor says about alcohol duty.

Cathy van Zyl MW

Does anybody in the room have any questions for Anthony?

Audience member

We have a huge crisis in shipping at the moment. We are exporting 15% more than we are importing, which is hugely exciting for us, but we have no shipping lines passing the southern tip of Africa at the moment. The wine industry is getting bumped all the time, because there are other exports that have to go out—perishables like citrus. And so it used to take us 21 days to get our wines to market in the UK and in Europe. And it’s now taking us four to eight months in some instances to get our wines around the world.

We get paid freight on board. So that means when the cargo leaves. Most of the big shipping lines in the world are European based. Now that you’re not part of Europe, is there anything that you could do to help us? We need to lobby government, we need the press to step in. We need everybody to get on board to make sure we get our wine is shipped around the world.

There was one other question: can we create a wine visa? Like you have a tech visa. There would be a lot of South Africans that would be very excited to make sure that we could help secure the future of fine wine in terms of sustainability.

HE Antony Phillipson

On the wine visa, I’m all for that. We have various types of different skilled workers, so I see no reason why we couldn’t create a separate route if we can’t use one of those already for filling the skills gap.

HE Antony Phillipson

I’m glad you mentioned shipping. One of the fundamental impacts of COVID has been to put a real shock through the supply chains. And if we ever have a shipping route really opening up across the Northwest, then probably that will reduce even more the prospect of container routes coming this way.

I don’t honestly know what the answer is to that other than really to echo something I said, which is governments will need to come together and deal with that. Especially if they’re dealing with cartel-like behavior. If we need to set global rules, then maybe we need to ask ourselves whether we have organisations that are fit for purpose. If we can’t do it in the WTO, can we do it in the International Maritime Organization? Can we do it in the OECD? That also emphasises a fundamental point, which is we need to hear from business as to what are the issues you’re bumping into, so that when we sit around those tables, we’re talking about the things that actually matter to you rather than things that actually will have no impact on your business whatsoever.

Audience member

Since you’re in a room full of movers and shakers here who are in the habit of actually turning good ideas into actionable steps, what would be some of your top tips from other practices you’ve seen of various forms of lobbying when you’re small and underfunded as a trade group compared to some of the big boys in tech? And would you have any suggestions for us of what we should do next to make sure that our needs are represented properly by our representatives like you?

HE Antony Phillipson

This won’t sound particularly sophisticated. I think the key thing when you come to lobby is, who holds the power in terms of who needs to make the decision that you need to have either changed or made in the first place? And then how do you access them and how do you influence them? As I said earlier, the reason why governments tend to go and retaliate or put retaliatory tariffs against the alcohol industry is because their sense that you are influential—you and the alcohol industry is important in the countries that you all operate in.

The reason why governments tend to go and retaliate or put retaliatory tariffs against the alcohol industry is because their sense that you are influential—you and the alcohol industry is important in the countries that you all operate in.

HE Antony Phillipson

In Washington, (industry) can tell a story about how they represent a large number of workers or if they are heavily located in key swing states when it comes to presidential elections.

I think that’s the same in the UK. The farming lobby is quite influential. It’s probably an outsized influenced compared to its percentage of the overall economy, because it is in every single constituency in the country and it has organizing power. That’s why the unions also, I think, continue to have influence, including in countries like South Africa. So I think it’s a question of what is it you need to focus on, who do you need? And then how do you access them? If you don’t feel you have representation at a trade association level, you mainly think about how you create it.

The key thing is when government comes along and says, “right, we’re thinking about writing a new policy on carbon tax or a new policy on the environment or a new policy on taxation”, make sure that your voice is around that table.

This discussion has been shortened and lightly edited.

This conversation is part of ARENI’s publication 12 Conversations: Different Ways of Looking at Sustainability, published in September 2022, available to all.